1 February 2026 by Dr Tim Coles

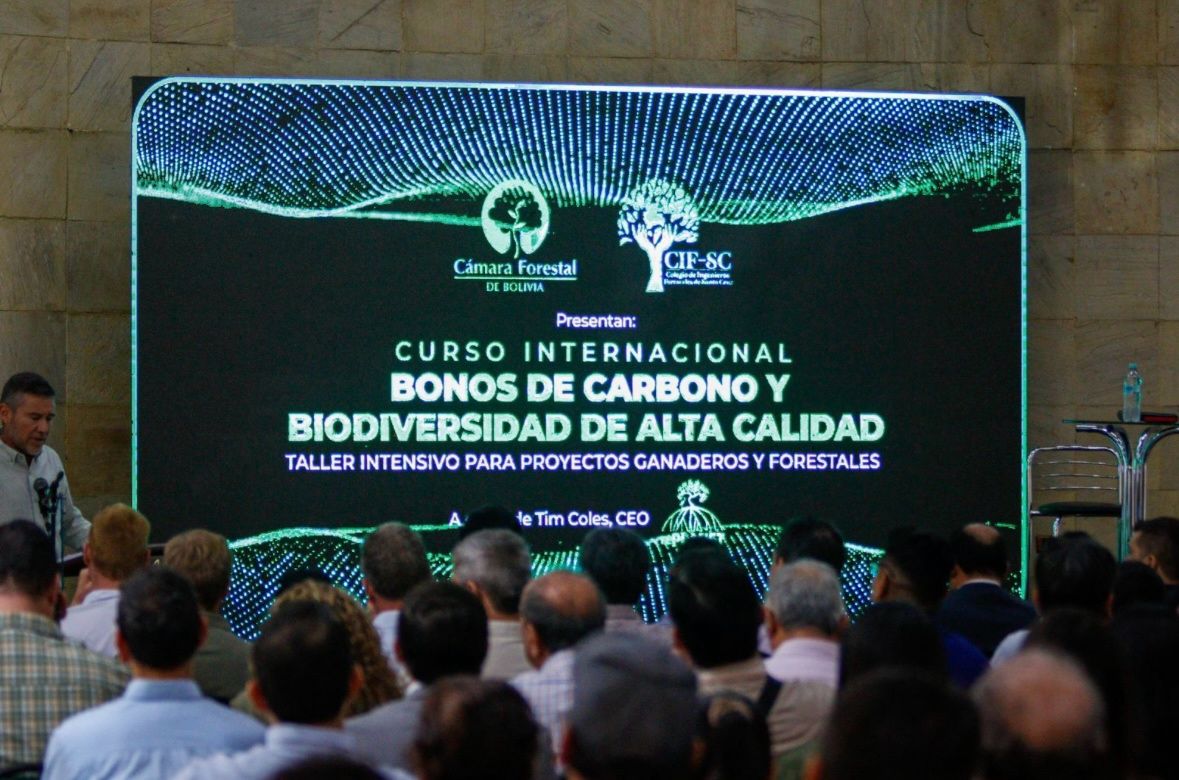

rePLANET Highlights from our International Course on Carbon Credits and High Quality Biodiversity Session

Dr Tim Coles shared three aspects that must be integrated into carbon credit funded nature-based solutions projects to effectively drive climate action.

Bolivia recently shifted its climate policy to engage with international carbon markets – transparency, strong MRV and permanence must be carefully factored into all new projects. It was brilliant to contribute to this event and see the great work happening across the community

Perspective of the International Couse on Carbon Credits and High Quality Biodiversity

Today I attended the International Course on Carbon Credits and High Quality Biodiversity, held at the Society of Engineers of Bolivia. The event featured the opening remarks of the Deputy Minister of the Environment, Jorge Ávila, who highlighted the importance of strengthening technical capacities around carbon markets and biodiversity conservation. There was also a presentation by rePLANET which generated a space for broad exchange, with many questions and answers, evidencing the interest and active participation of the attendees.

This course was organized by the Ministry of Development Planning and Environment in coordination with the ABT – Autoridad de Fiscalización y Control Social de Bosques y Tierra and rePLANET, reaffirming the commitment to training and dialogue for responsible environmental management. Continuous training is key to addressing today’s environmental challenges.

When Tim Coles talks about carbon, he doesn’t do it from the pulpit of abstract environmentalism or from the coldness of a financial spreadsheet. His tone is slow, didactic, almost domestic. But behind that calm there is a disruptive proposal: to transform traditional livestock farming into an ally of forest restoration and turn this transition into a profitable, measurable and attractive business for large global buyers of carbon credits. Coles is an environmental scientist, with more than four decades dedicated to designing and financing nature-based solutions.

Today he leads rePLANET, a company that works with high-quality carbon and biodiversity credits and already has operational projects in countries such as Costa Rica and Panama. His career combines rigorous science and market logic, an uncommon mix but increasingly in demand in a world that seeks to mitigate climate change without sacrificing production or development.

“The key is to understand that this is not against the producer,” he explains. “On the contrary: if you don’t make more money than before, the model doesn’t work. Their approach is based “on a simple and forceful premise: improve livestock productivity through rotational grazing, free up part of the land and use that space to restore native forest that, in turn, generates high-value carbon credits. Rotational grazing, he explains, involves moving from an extensive system to a more efficient one, in which cattle rotate between pastures.

“With that, the same or more can be produced, but in less area,” he points out. This change frees up between 5% and 30% of the farm, an area that is destined for reforestation and wildlife corridors. “It’s not about taking land away from the rancher, it’s about reorganizing it so that it produces better,” he sums up. The incentive is not minor. According to Coles, the projects that rePLANET develops invest in the farm from the beginning: fencing, water systems, technical assistance and training. From the fourth year, direct payments per hectare reforested begin. “With current projections, we are talking about around 400 dollars per hectare per year for decades,” he explains. It is not philanthropy: it is an investment that competes with traditional income from production.

But the real differential is in the type of carbon that is generated. Coles is categorical in distancing himself from conventional projects. “A common carbon credit sells for $15 or $20. A high-quality one can go up to 90,” he states. The difference? Three non-negotiable conditions: that at least 60% of the profits remain in the hands of local actors; that biodiversity is measured and a real increase of the order of 50% is demonstrated; and that the farm produces the same or more food than before. This high standard is what arouses the interest of large buyers. Companies linked to aviation and the aeronautical industry, pressured by their climate commitments, are looking for reliable, permanent loans with a social impact. “They don’t want cheap, dubious carbon anymore,” Coles says. “They want projects that stand up to audits and public scrutiny.” The same goes for tech giants whose data centres consume huge amounts of energy and need credible trade-offs.

The impact is not limited to the individual producer. At the centre of the model is also the community that inhabits and cares for the forests. “If the benefits don’t reach the local people, the system fails,” he insists. Hence its emphasis on clear rules and independent verification. International experience has taught him to be wary of shortcuts: poorly designed “avoided loss ” or protection projects for existing forests have damaged market reputations and plunged prices.

“Today they are worth one and eight dollars. That does not change realities,” he warns. His proposal is committed to restoration: recovering areas degraded more than a decade ago and returning them to a native, diverse and permanent forest. To this end, fast-growing pioneer species are used that facilitate the subsequent establishment of native species. “It’s more expensive, yes, but it’s also much more valuable,” he explains. In terms of carbon and biodiversity, the difference is directly reflected in the price. Coles speaks enthusiastically, but without grandiloquence. His style is that of a teacher explaining a complex problem with concrete examples.

However, the ambition of the project is enormous: to reorder the relationship between production, conservation and the market. “For years it was believed that burning forest was the only way to generate economy,” he reflects. “We show that there is a more profitable and sustainable alternative.” The bet is aggressive in objectives and scale, but it is based on a simple logic: if the forest is worth more standing than burned, someone will take care of it. And if that care translates into stable income for producers and communities, the model ceases to be an environmental discourse and becomes a real economic option. That is, in essence, the proposal that Coles is putting on the table today.